On the night of January 23, 1982, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 approached Boston Logan International Airport in the middle of a winter ice storm. The runway lights were visible. The surface looked usable. Nothing suggested the landing would end anywhere other than the pavement.

Moments later, the aircraft was sliding uncontrollably toward Boston Harbor.

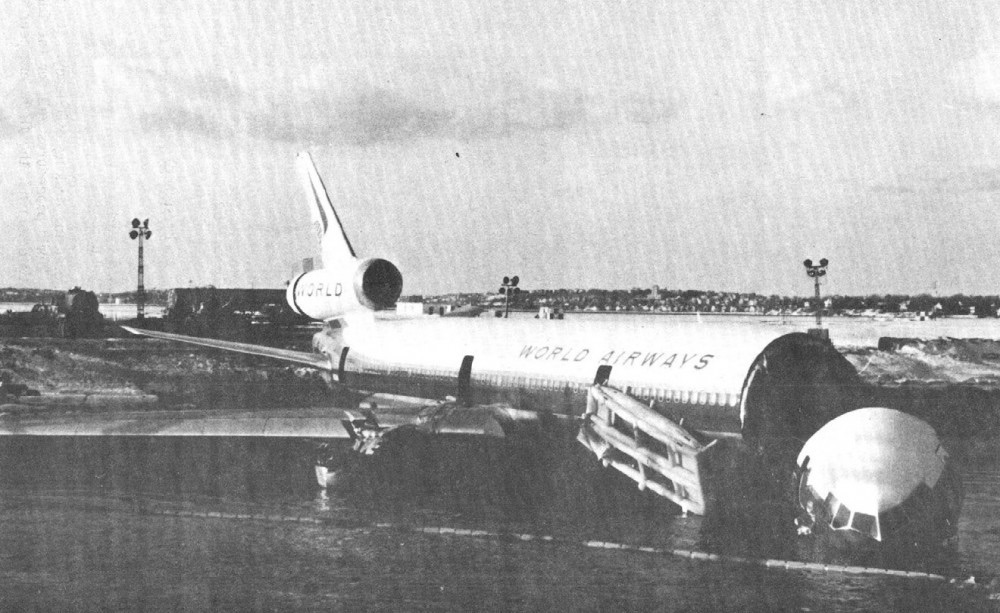

The jet was operated by World Airways and carried 212 people. When it finally came to rest in the frigid water just beyond the runway end, 210 survived. Two passengers were never found.

The approach that looked routine

World Airways Flight 30H was inbound to Boston from Newark late in the evening. Snow and freezing precipitation had been affecting the airport throughout the night, but arrivals were continuing.

Runway 15R appeared open and serviceable. There was no immediate indication to the crew that braking effectiveness had deteriorated to a critical level.

What the pilots could not see from the cockpit was how quickly runway conditions had changed.

Touchdown and the loss of braking

The DC-10 crossed the threshold of Runway 15R and touched down well beyond the displaced threshold, leaving significantly less usable runway than normal. Almost immediately, the crew realised something was wrong.

Braking effectiveness was minimal. The aircraft did not decelerate as expected. Reverse thrust and braking inputs produced little result as the jet continued to slide.

With the runway rapidly disappearing, the crew faced a final decision. Continuing straight ahead risked striking approach light structures. Steering off the paved surface offered the only remaining option.

The aircraft veered right and overran the runway, sliding into shallow water at the edge of Boston Harbor.

Wreckage of World Airways Flight 30 (McDonnell Douglas DC-10, registration N113WA) after overrunning Runway 15R at Boston Logan International Airport and coming to rest in shallow water, January 23, 1982. Photo public domain, courtesy of the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board.

Impact, evacuation, and freezing water

The DC-10’s nose section separated as it entered the water. Fuel spilled, and the aircraft began taking on water almost immediately.

Cabin crew initiated an evacuation in darkness and freezing conditions. Passengers climbed onto wings, escaped onto nearby structures, or waded through icy water as emergency services responded.

Despite the severity of the accident, most of those on board survived. Two passengers were later listed as missing and presumed drowned, their bodies never recovered.

Why the runway “looked fine” but wasn’t

In the hours leading up to the accident, pilots who had landed before Flight 30H reported rapidly degrading braking conditions, ranging from “poor” to “poor to nil.”

Those reports mattered. But they did not reach the cockpit in time.

According to the investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board, the airport’s assessment of runway conditions lagged behind reality. The automatic terminal information service was not updated to reflect the most recent braking reports, and air traffic controllers did not pass along the latest pilot feedback to the arriving crew.

From the flight deck, the runway still appeared usable. The critical information that would have changed the crew’s expectations never arrived.

What the NTSB found

The NTSB did not blame the accident on pilot error or aircraft malfunction. Instead, the final report pointed to a chain of systemic failures.

Investigators cited:

Severely reduced braking effectiveness caused by ice contamination Inadequate runway condition assessment by airport management Failure to promptly update and disseminate braking action reports The decision to keep the runway open despite deteriorating conditions

In simple terms, the system that should have warned crews that the runway was no longer safe did not work as intended.

World Airways DC-10 (registration N113WA) up on blocks shortly after its accident at Boston Logan International Airport in early 1982. Photo by Eddy C, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Why this accident mattered beyond Boston

At the time, braking action reporting relied heavily on subjective pilot reports and delayed surface inspections. There was no standardized, real-time way to communicate how contaminated a runway actually was.

The World Airways overrun became one of several winter accidents that exposed the limits of that system.

In the years that followed, regulators and airports began pushing for clearer procedures, better runway condition assessments, and improved communication between airport operators, controllers, and flight crews.

Those lessons eventually fed into the development of more standardized runway condition reporting methods used today.

Could this happen again?

Modern airports now use improved surface measurement techniques, standardized reporting formats, and more aggressive runway closure policies during severe winter weather.

That does not mean the risk has disappeared.

Runway overruns remain one of the most common categories of serious aviation accidents, particularly during winter operations. What has changed is how quickly deteriorating conditions are identified and communicated.

The central lesson from Boston in 1982 remains the same: a runway that looks usable can become unsafe faster than crews can react if critical information does not reach the cockpit.

The human cost behind the investigation

For investigators, Flight 30H became a case study in systems and procedures. For passengers and families, it was something else entirely.

Two people boarded a flight that night and never returned home. Their disappearance is a quiet footnote in aviation history, but it is the reason the accident is still remembered decades later.

Every change in winter runway operations that followed traces back, in part, to nights like that one at Boston Logan.

Why the story still matters

This accident is not remembered because of dramatic images or aircraft damage alone. It is remembered because it showed how easily a chain of small communication failures can overwhelm even a large, capable aircraft.

Forty-four years later, the lesson remains uncomfortably relevant. In aviation, the most dangerous runway is often the one that looks safe.