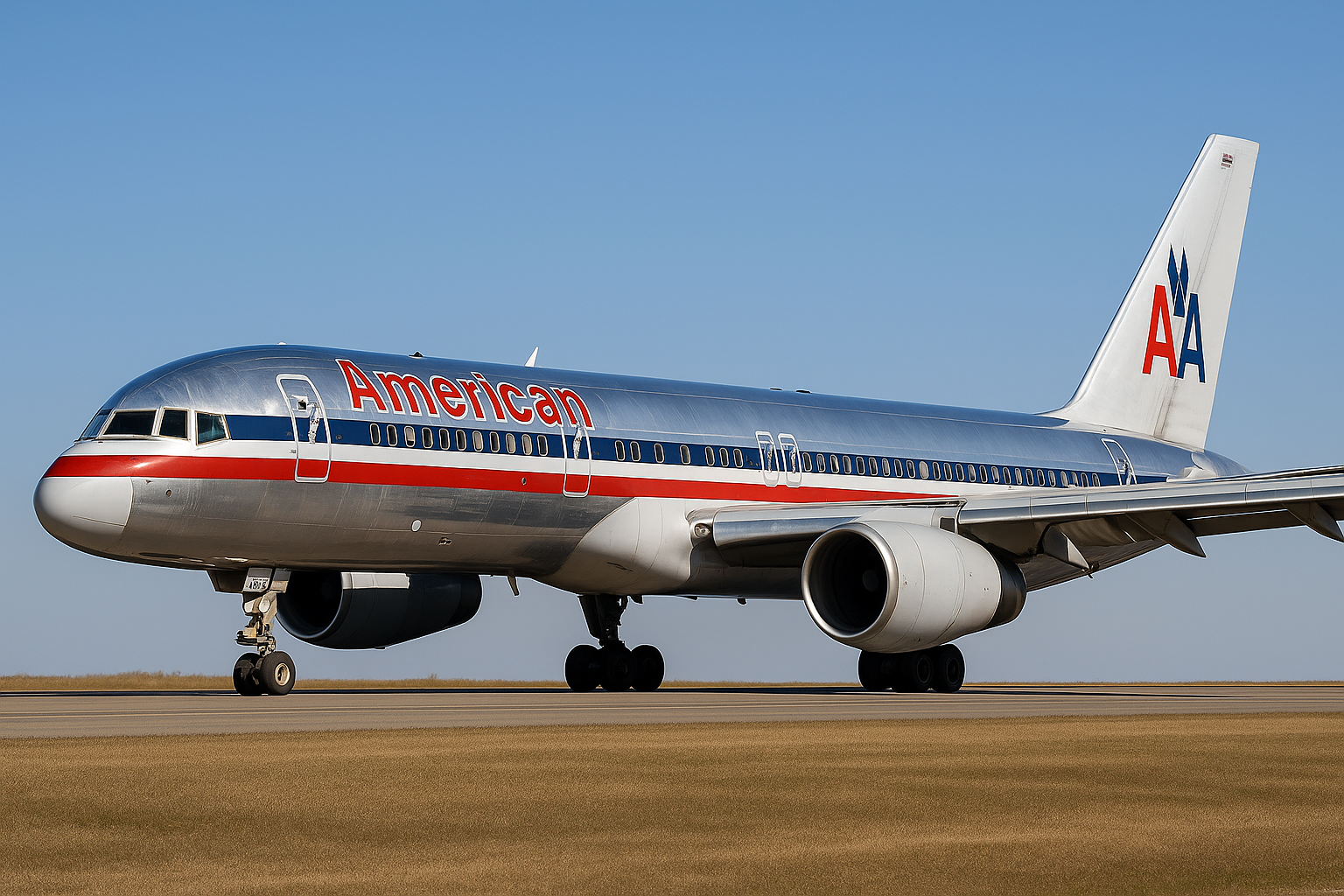

Freighter ramps commonly feature Boeing 747‑400s, DC‑10s, or Airbus A300s that remain in active service. Many of these aircraft first entered operation decades ago, predating the careers of current cargo pilots. IATA’s 2024 fleet analysis reports that passenger aircraft average 13 years of age, while cargo aircraft average 25 years. This significant age gap results in many cargo airplanes being older than the pilots operating them. The persistence of older jets in cargo fleets is driven by economic considerations, utilization patterns, safety regulations, and the particular requirements of freight operators.

This article examines the age disparity between cargo aircraft and their pilots, analyzes the economics of operating older airframes, investigates passenger‑to‑freighter (P2F) conversions, and considers the future of freighter fleets. All claims are supported by reliable sources to secure accuracy and credibility.

The Age Gap: Aircraft vs. Pilots

How old is the cargo fleet?

- Average cargo fleet age: IATA reports that the global cargo fleet averages 25 years, nearly double the passenger fleet’s 13‑year average. Age categories show a concentration of cargo aircraft between 30 and 35 years old, showing a reliance on legacy platforms.

- Supply‑chain delays: A 2025 IATA report on the global fleet notes that aircraft deliveries remain behind schedule, forcing airlines to retain aging equipment longer than planned and delaying fleet renewal. Manufacturing backlogs exceeding 17,000 aircraft mean replacement jets may not arrive until the early 2030s.

How old are the pilots?

- Pilot demographics: The FAA’s 2024 statistics show that more than 30 % of for‑hire pilots are between 50 and 64 years old. Stratus Financial’s 2024 pilot‑shortage report cites FAA data estimating the average commercial pilot at 45 and the average airline pilot at 49.

- Mandatory retirement: U.S. law requires pilots to retire at age 65. Many cargo captains fall well below this age, making it common for their aircraft to pre‑date them by a decade or more.

Age gap summary

| Cargo aircraft | ≈25 years | Many freighters are passenger conversions; the most common age bracket is 30–35 years. |

| Passenger aircraft | ≈13 years | Airlines renew fleets sooner for fuel efficiency and passenger comfort. |

| For‑hire pilots | ≈45–49 years | Roughly one‑third of working pilots are aged 50–64. |

| Mandatory retirement | 65 years | Pilots must retire at 65, so aircraft older than that are flown by younger pilots. |

The data point up the disparity: many cargo aircraft are older than the pilots who operate them.

Economics: Why Old Planes Make Sense for Cargo

Acquisition and capital costs

Cargo carriers operate on thin margins. Purchasing a factory‑new freighter like Boeing’s 777‑8F or Airbus’s A350F costs over US $150–200 million. Converting a used passenger jet into a freighter costs about US $25 million, while converting a Boeing 767 costs US $40–50 million, saving 60–75 % compared with buying a new aircraft. These lower capital costs free up cash for route expansion and reduce depreciation.

Utilization patterns

- Lower flight hours: FAA utilisation statistics show that all‑cargo aircraft fly 4.6 hours per day on average, whereas passenger jets log 8.5 hours per day. Narrow‑body freighters average just 2.9 hours daily.

- Fewer cycles: Cargo missions frequently involve fewer take‑offs and landings than passenger flights. Lower cycle counts reduce structural fatigue, enabling airframes to remain in service longer.

- Pilot duty hours: Cargo pilots average 31 block hours per month compared with 57 hours for passenger pilots. Lower utilisation reduces crew fatigue and extends aircraft life.

Operating costs vs. fuel burn

Older jets burn more fuel and require more maintenance. However, when used aircraft cost a fraction of a new one and fly only a few hours per day, higher fuel consumption is offset by minimal capital expense. According to a recent IATA report, airlines are continuing to use older, less fuel-efficient aircraft due to delays in new aircraft deliveries, which results in higher fuel costs.

Passenger‑to‑Freighter Conversions: Extending Life and Saving Money

Passenger‑to‑freighter (P2F) conversions underpin the cargo fleet. Airlines retire passenger aircraft after 15–20 years because of rising maintenance costs and fuel inefficiency, yet many of these jets have considerable structural life remaining.

How conversions work

During a P2F conversion, seats and cabin furnishings are removed, structural supports added and a large cargo door installed. The Flying Engineer explains that such conversions can extend a jet’s life by 10–15 years. Older Boeing 767s and Airbus A330s are common candidates, then serve cargo carriers after passenger airlines retire them.

MarketMarket forcesmmerce boom: IATA’s cargo recovery report notes that demand for air freight surged in 2024 due to strong e‑commerce and disruptions in sea shipping. Cargo yields remained 46 % above 2019 levels, supporting investment in freighters.

- Feedstock scarcity: The KPMG Aviation Leaders 2025 report warns that re‑activating older aircraft during post-pandemic rebound has reduced feedstock for conversions. Lessors sometimes earn more by leasing engines than converting entire aircraft. Feedstock shortages mean cargo carriers hold onto old jets instead of retiring them.

- Cost advantage: Etihad Cargo notes that converting a passenger aircraft costs roughly US $25 million versus US $150–200 million for a new freighter. These conversions provide a cost‑effective way to add capacity quickly when new‑build production slots have four‑ to five‑year waits.

Economic benefits

| New 777‑8F / A350F | US $150–200 M (list price) | 30 years | High efficiency but long lead times. |

| P2F conversion (e.g., 767‑300ER) | US $25–50 M | 10–20 years | Extends life with 60–75 % savings. |

| Continue operating older freighter | Minimal capital cost | Varies | Higher fuel burn but avoids capital expenditure. |

Conversions therefore provide a financially viable alternative to purchasing new aircraft or continuing to operate significantly aged airframes.

Operational Facts: Why Cargo Doesn’t Need New Cabins

Cargo carriers prioritize payload capacity and functional dependability rather than passenger comfort. Numerous operational factors add to the suitability of older jets for freight operations:

- No cabins to maintain: Freight carriers avoid costs associated with cabin refurbishments, in‑flight entertainment and passenger amenities. This eases maintenance and reduces upgrade pressures.

- Flexible timetabling: Many cargo flights operate overnight, when airports are quieter. Lower utilisation means the aircraft are not scheduled to fly back‑to‑back 12‑hour cycles like passenger jets.

- Noise and emissions compliance: Older aircraft must meet International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) noise standards (Stage 3 or 4) and emissions rules. Carriers often retrofit hush kits and engine modifications. However, IATA warns that older cargo aircraft hamper decarbonization efforts because their fuel efficiency is lower.

Safety: Are Old Planes Riskier?

Safety cannot be compromised regardless of aircraft age. Studies consistently show no correlation between aircraft age and accident rates. According to Pilot Institute, incidents involving structural failure in older aircraft, such as the Aloha Airlines Flight 243 accident, were largely caused by undetected issues like fatigue cracks rather than the plane’s age itself. The article also notes that aviation safety regulations require the same inspections for both old and new aircraft. The Flying Engineer notes that a well‑maintained 25‑year‑old aircraft must meet the same airworthiness requirements as a brand‑new one, with maintenance checks becoming more frequent as the plane ages.

Regulators also limit pilot age; U.S. law mandates retirement at 65 years, ensuring pilots remain medically fit. Thus, cargo airlines’ use of older aircraft does not imply relaxed safety standards.

Case Study: The Boeing 747‑400F and the New Era

The iconic B747‑400F remains widely used despite production ending in 2023. Leschaco’s freight analysis notes that the 747‑F is still prized for its 112‑ton payload and nose‑loading capability, but its operational performance is outdated. Even Cargolux, with one of the largest 747 freighter fleets, plans to replace them with Boeing 777‑8Fs. Next‑generation freighters like Boeing’s 777‑8F and Airbus’s A350F promise 30 % lower fuel burn per ton and payloads comparable to the 747. The first 777‑8Fs are due for delivery in 2028, and the A350F enters service in 2027. Till these arrive, airlines continue flying older freighters.

Environmental and Policy Considerations

Aging cargo fleets complicate aviation’s decarbonization goals. IATA’s 2024 report warns that the high share of older aircraft has stalled the historical trend of increasing fuel efficiency; fuel consumption per tonne‑kilometer remained flat in 2024. Older engines burn more fuel and emit more CO₂, offsetting gains from sustainable aviation fuels or operational optimizations. According to the Federal Aviation Administration, new rules will require improved fuel-efficient technologies for airplanes manufactured after January 1, 2028. While proposals like “cash-for-clunkers” programs and higher carbon taxes on fuel-inefficient aircraft are intended to speed up the retirement of older freighters, industry operators caution that, without a sufficient supply of new jets or conversions, taking older aircraft out of service too soon could lead to capacity shortages.

Why Do Cargo Airlines Keep Flying Old Jets?

Bringing all factors together, cargo airlines continue flying aircraft older than their pilots because:

- Capital efficiency: Purchasing used passenger jets and converting them is far cheaper than buying new freighters.

- According to IATA, the average age of widebody freighters is currently 19.6 years, highlighting how conversions can extend aircraft life and support fleet flexibility for cargo carriers.

- Safety parity: Maintenance standards for old planes are identical to those for new ones, and pilot retirement rules ensure crews remain medically fit.

- Supply bottlenecks: Production delays and long delivery backlogs force airlines to retain aging aircraft. The return of stored aircraft has reduced feedstock for conversions, so operators have little choice but to continue flying older jets.

Looking Forward

The next decade will usher in a new generation of purpose‑built freighters. Boeing’s 777‑8F and Airbus’s A350F ensure substantial fuel‑burn reductions and are already attracting orders. However, their deliveries will not ramp up until the late 2020s. Until then, cargo airlines will lean on conversions and legacy jets to meet booming e‑commerce demand. Government officials and business executives must balance emission goals with the reality of constrained supply.

What this means for readers

An analysis of cargo airlines’ reliance on older aircraft reveals a complex interplay among economic elements, regulatory requirements, and environmental objectives. The continued operation of vintage freighters is not due to a disregard for modern technology, but instead reflects sound business rationale and observance of safety standards.